Singer, Actor, Composer and Eccentric – the Many Lives of Kishore Kumar

A detailed biography of the singer, Kishore Kumar which is strong on anecdotes but falls short on context.

Kishore Kumar is an undying talisman of Hindi cinema. Actor, producer, lyricist, composer, prankster; he could put on several hats. As could many others. But barely anyone else could, with such full-throated ease, bring as much jouissance to a song of spring as he could bring heart-breaking melancholy to that of a forlorn winter. This is beyond the rank of doubt.

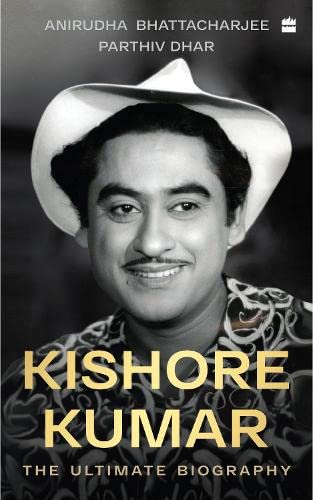

What cannot readily be agreed upon, however, is what kind of biography he would lend his life to. Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Parthiv Dhar’s Kishore Kumar: The Ultimate Biography is a focused biography and not a cultural history, and hence short on context. For example, 1950s Hindi cinema (and that cinema’s music) was an extraordinary constellation of talents, who were not just versatile but also brought their own tongues, cultural nuances and ethos to the industry. The book is unable to highlight this aspect, which hurts its overall appeal.

Instead, what the authors are comfortable with, perhaps understandably so, is how many whistles per minute Kishore’s life had – i.e. the smaller details, even trivia. And one must give it to the authors that they have managed to keep the pace in this book going right from the beginning, crowding each page with anecdotes they considered worth retelling. To that end, this bulky book points to one possibility of a thorough, if mostly anecdotal, biography.

It would have been very different if Kumar were alive, for the book would have shaped up with his presence in mind. Since he is not, the argumentative structure of this biography seems to follow a pattern, which can be called persuasion by evidence. This means that at each step the authors have cited facts and testimonials, whether collected by them or collated from existing sources. And in doing so, Bhattacharjee and Dhar have taken the archaeologist’s method to look for their absent subject. They carried their shovel to wherever they found clues, and started to dig as deep as they could. And whatever they found, portentous or insignificant, they used their trowel to clean it up and save it for preservation.

The amount of legwork that has gone into this book demands praise, especially in an environment where hard-boiled research is usually given a short-shrift. The result is a fact-heavy biography, written in bursts of innumerable short passages pressed together. It has also followed the birth-to-death progression of Kishore, which is broken, time to time, by brief, non-linear interludes.

Another kind of interlude is provided by tacky ‘artist’s impressions’, sketches that I found somewhat annoying. The accompanying photographs, of which there are several, are well-sourced and diligently annotated. They add value. The drawings don’t.

Since the authors have diligently taken to their job of detailing a life as exhaustively as possible; the family history is given enough space, and so are Kishore’s growing up years at Khandwa in Madhya Pradesh. Here one bit is amusing. The authors claim that the family of the Gangolys (as spelt then) can be traced to Raghu, a legendary, Robinhood-like burglar of pre-modern Bengal. The link is tenuous at best, but for me, the connection reads like an allegory.

Kishore, the swashbuckling singer and yodeller, who would gate-crash cinema soundtracks, overwhelm its classical gatekeeping and establish a legacy uniquely his own, could well be tracing his genes to one such trespasser a couple of centuries ago. Khandwa also seems to be an imaginary space in Kishore’s life – a space of retreat and recluse, which is captured well.

Another constant in Kishore’s life – both real and imagined – was Ashok Kumar (the leading screen actor, producer, studio mogul till the early 1950s), his big brother in more sense than one, for he hovered over Kishore’s life even when he was not. On the other end of it is Amit Kumar, who seems to be totally absent. One cannot but ask, why was it that the authors got access to the most unlikely of sources in Kishore’s life, and yet Amit Kumar eludes them throughout the book?

The biographers never lose sight of Kishore though, and the section where they throw adequate light is when they focus on Kishore’s acting life in the 1950s. Populated with filmic minutiae, innumerable names and industry chatter, this section unearths relatively lesser known parts of Hindi cinema history.

Kishore was a busy comic-actor for many of these years and the film that stands out is Naukri (954), Bimal Roy’s tragicomic film about finding a decent livelihood. There were two others, both of which came in 1958: Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi, the goofy comedy, where Kishore’s voice merged famously with the madcap plot; and Lukochuri, Kishore’s only memorable Bengali film, where he had sung a cult romantic duet with his just-estranged wife Ruma Guhathakurta.

Otherwise, Kishore didn’t particularly like the rigour of acting, the book says, and the soundtrack that came his way, keeping with his screen persona, was of the lighter variety. Kishore regaled in this genre but was anxious not to be caged by it. After all, one of his finest renditions of pensive gloom – ‘Dukhi Man Mere’ (Funtoosh, 1956) – came during this time, sadly without changing things much. Songs that could push his vocal range and try his timbre, so to say, took time to come.

Circumstances, personal matters and the embedded volatility of the cinema industry ensured that Kishore emerged into full bloom not before the mid-1960s. While progressing towards those years of triumph, the authors stop by almost each song, interspersing them with accounts of his personal life. The Madhubala episode, needless to say, is unhappy for both of them. Together, much of the book provides some idea of the various personas that Kishore had. What is revelatory, not entirely surprisingly, is Kishore’s range.

One must just put Half Ticket (1962), Aradhana (1969), Mili (1975), and Aandhi (1975) next to each other (among numerous others) to fathom that impossible was not a word in Kishore’s lexicon. It comes indeed as no surprise, then, that he refused to bow down to the silly diktats of the Emergency. When did Kishore live by terms set by others anyway? He also died like that; choked by a sudden, fatal cardiac arrest on an otherwise fine day in October 1987.

Just like the deficiency in setting a context, one is disappointed that there is no reflection on Kishore’s remarkable, ever-renewable afterlife. After all, this book comes 35 years after his death. But the authors are so conscious never to take upon a narratorial voice independent of facts, these reflective details have all remained absent, unlike the very present protagonist. To that end, one misses a touch of flourish in a man’s life story who sang so poetically about zindagi in all its piquant possibilities.

Sayandeb Chowdhury teaches at Ambedkar University Delhi.